Exploring Shamanism: A Global Tapestry of Animism and Spiritual Connection

Journey through the ancient practices and modern relevance of shamanic traditions worldwide

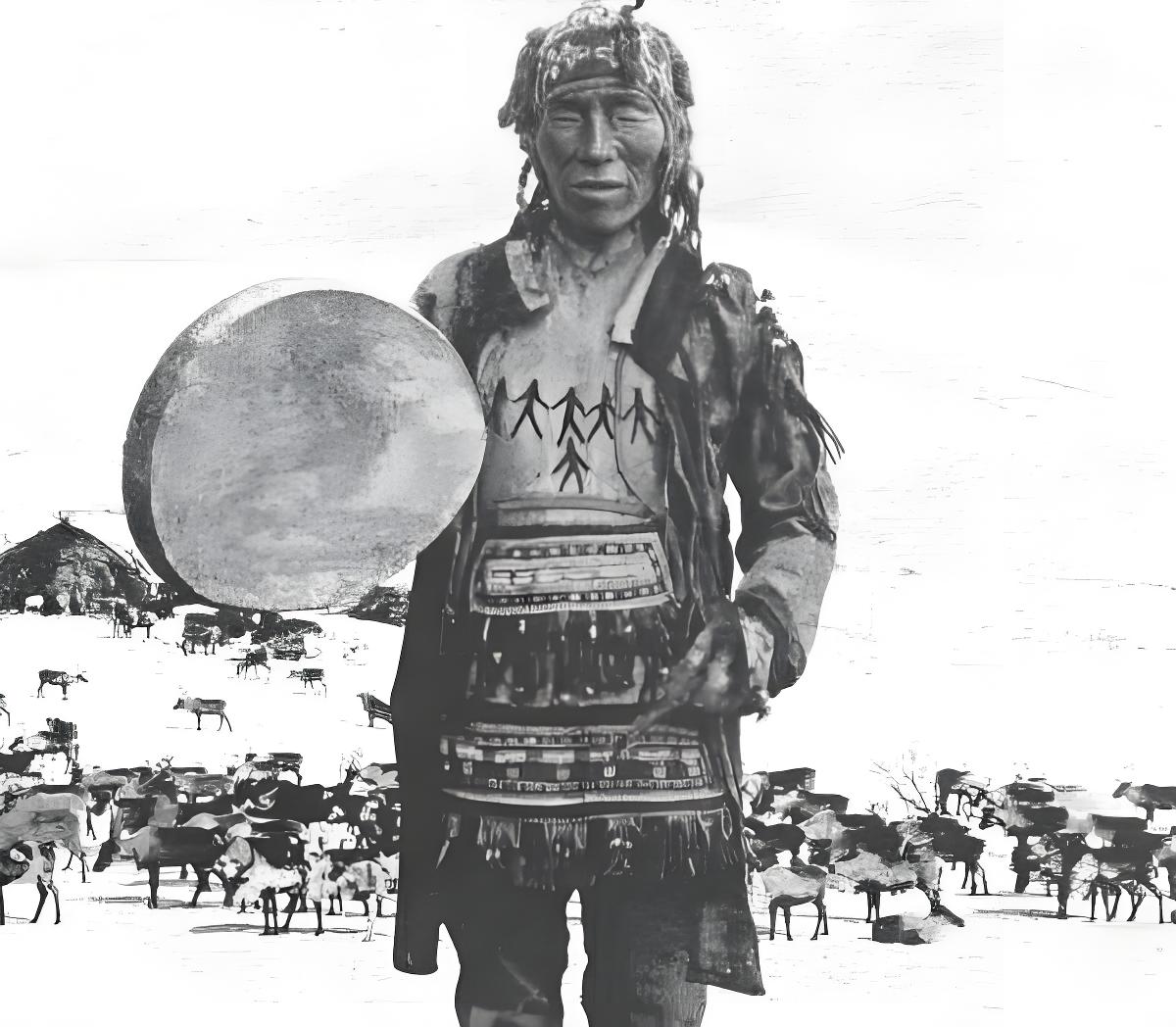

Shamanism, derived from the Jurchen term "Shaman" (now an international concept), represents a profound and globally dispersed folk culture centered on animism—the belief that all living and non-living entities possess a spirit or essence. Contrary to common misconceptions, there is no "Shamanism religion"; rather, shamanism is a practice carried by individuals acting as intermediaries between the human world and the spiritual realm. This blog delves into the history, worldview, and cultural significance of shamanism, drawing insights from its diverse expressions across continents.

1. Shamanism Through Western Eyes: A Journey of Misunderstanding and Rediscovery

European encounters with shamanic cultures began in the 16th century when colonizers in the Americas and Siberia encountered indigenous practices rooted in nature worship and spirit communication. Early Christian missionaries, such as Russian Orthodox priest Stepan Stepanovitch Stennikov, dismissed shamans as "devil summoners," reflecting religious biases against anything outside monotheistic norms.

By the 18th century, Europeans viewed shamanism as mere "magic" or trickery. It was not until the 19th century that anthropologists began to recognize its cultural legitimacy, though often framing it as a primitive practice of "uncivilized" societies. A pivotal shift occurred in 1951 with Mircea Eliade’s Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy. Despite flawed comparisons (e.g., linking shamanism to Tibetan Buddhism’s esoteric practices), Eliade’s cross-cultural research highlighted universal symbols like the "world tree" and "spirit ladders," and sparked interest in shamanism’s connection to plant medicine (e.g., hallucinogenic herbs in Mexican rituals).

The 1960s hippie counterculture further popularized shamanic aesthetics, blending indigenous symbols with spiritual curiosity. Today, shamanism continues to inspire global interest, from academic studies to New Age practices.

2. The Shaman’s Worldview: Bridges Between Realms

At the core of shamanism lies the shaman’s role as a spiritual mediator. Through trance states or spirit possession, shamans traverse the boundary between the physical and spiritual worlds. Trance, often induced by drumming, dance, or plant substances, allows shamans to communicate with helper spirits—entities that guide, heal, or reveal knowledge. For example:

- In Inuit culture, spirits (tornait) manifest as humans, stones, or animals, selecting individuals to become angakkuq (shamans). These chosen ones undergo purification rituals (fasting, vomiting) to prepare for their role.

- Siberian Yukaghir shamans, as documented in Soul Hunters, use ceremonial mimicry (e.g., imitating elk movements) to invoke hunting success, emphasizing harmony with nature.

A key debate surrounds whether shamans are "mentally ill" or spiritual healers. Psychologist George Devereux once pathologized their states, while anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss argued they function as "spiritual analysts," interpreting symbolic dreams and visions to address communal needs.

3. Shamans as Healers, Hunters, and Cultural Custodians

Shamans historically served practical roles:

- Hunting Magic: In Sichuan’s Yutong culture, "droppers" used spells and traps to sustainably hunt, blending practical skills with ritual. Yukaghir shamans like the author’s mother in Soul Hunters entered trances to locate game, emphasizing ethical harvesting.

- Healing: Shamans often acted as traditional medical practitioners. For instance, Alaskan Yupik shamans performed exorcisms to rid patients of malevolent spirits, while Amazonian curanderos use plant diets to address physical and spiritual ailments.

Modern shamans adapt these roles to contemporary needs, focusing on ecological balance and mental well-being. As Michael Harner describes in The Way of the Shaman, his ayahuasca journey in the Amazon revealed a universal "hidden world" of spirits, inspiring his work to preserve shamanic knowledge globally.

4. Shamanism Tradition and Modern Revival

China’s diverse ethnic groups host rich shamanic traditions:

- Northern Practices: Among the Oroqen and Evenki, "spirit possession" rituals involve drumming and ancestor veneration, with shamans (e.g., chuonnasuan, the last Oroqen shaman) serving as cultural custodians.

- Southern Rituals: "Climbing the knife mountain" ceremonies in southern provinces embody shamanic courage and spiritual prowess, blending martial and mystical elements.

Today, shamanism in China navigates dual perceptions: once dismissed as "rural superstition," it now thrives in urban subcultures, with young people embracing drumming circles and ceremonial practices as tools for mindfulness and connection to heritage.

Conclusion: Shamanism as a Mirror to Humanity’s Relationship with Nature

Shamanism is more than a historical curiosity; it is a living tradition that challenges modern societies to reconsider their place in the natural world. From Siberian tundras to Amazonian rainforests, shamans remind us of the interconnectedness of all life—a wisdom increasingly vital in an era of ecological crisis. As we embrace cultural pluralism, let us honor shamanism not as a relic, but as a profound dialogue between humanity and the animate universe.