The Spiritual Echo in Nomadic Civilization: Exploring the Hidden Veins of the Shamanic World

In the snowy wastelands of Siberia and the wind-swept grasses of the Mongolian Plateau, the ancient beliefs of nomadic peoples flow like a hidden river through the depths of human civilization. In the words of Where the Mountains and Rivers Sing: Tuva Music and Nomadic Life, the purification ritual of the Tuva shaman Lazo unfolds like a vivid scroll, lifting the veil on the mysterious world of shamanism.

I. Sacred Dialogue in Ritual: The Resonance Between Shamans and the Spirit Realm

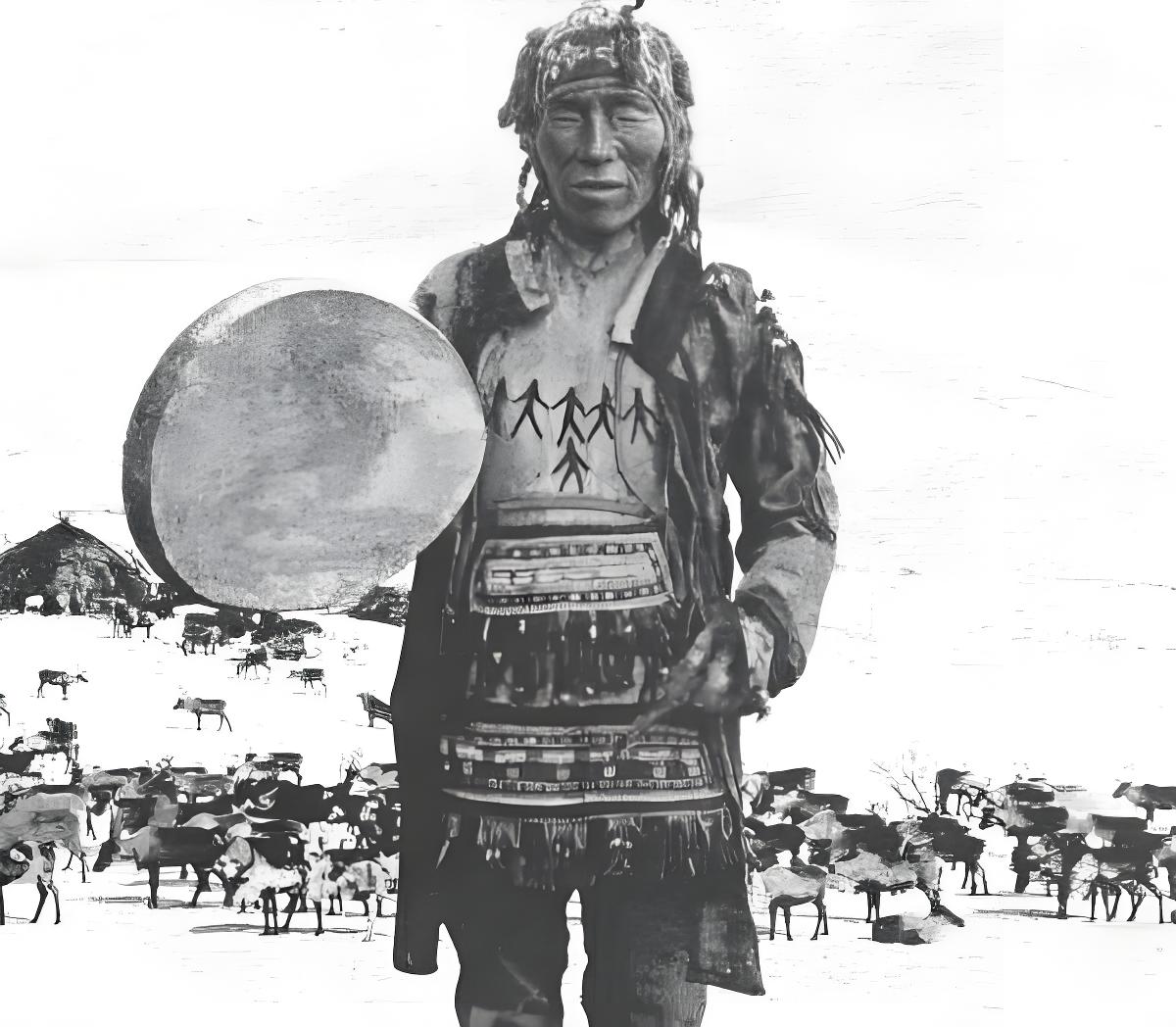

Clad in garments adorned with bird feathers, bells, and colorful cloth strips, with a wolf skull hanging at the center of his back, Lazo tightens the skin of his shaman drum over a fire, ensuring its sound is crisp and powerful. As he circles the fire, leaping and chanting monotonous beats, he calls for souls to return to their rightful places. This is not merely a religious ceremony but an ancient cipher through which nomadic peoples communicate with all things in nature. Bird feathers symbolize a connection to the sky, while the wolf skull embodies reverence for wild power. The vibrations of the shaman drum act as a key to unlock the doors of the spirit realm. Through physical rhythm and vocal resonance, this ritual weaves the human world and the supernatural into a network of energy, embodying the core nomadic belief in "animism"—that every mountain, river, plant, and stone possesses a soul.

II. The Philosophical Mirror of Multi-Realm Views: Spiritual Coordinates in Parallel Universes

The Sámi belief in two realms (the human world and the lower world) and the Mongolian-Tuva system of three realms (upper, human, and lower) form a geometric blueprint of the nomadic spiritual world. The concept of overlapping realms echoes modern physics' theory of parallel universes but was already a philosophical framework for nomadic peoples millennia ago. Ordinary humans are bound by the perceptions of the material world, while shamans, as "spiritual ferrymen," traverse these realms, transmitting messages across dimensions. This worldview not only shaped nomadic explanations of life, death, illness, and natural phenomena but also gave birth to unique art forms: the Sámi joik songs murmur like the wind, Tuva and Mongolian khoomei (throat singing) mimic the reverberation of mountains, and the khomus (jaw harp) trembles like whispers from the spirit world—all essentially serving as mediums across realms.

III. The Trials and Survival of Faith: Cultural Resilience in the Tide of Modernity

The millennial journey of shamanic beliefs is interwoven with glory and vicissitudes. When Christian missionaries denounced it as "Satanic," when the "civilizing offensives" of the Communist era sought to erase traditions through schooling, and when modern snowmobiles replaced reindeer sleds, the ancient faith scattered like dandelions in a storm. Yet on the snowfields of Murmansk, there are still Sámi like Nikolai Kalugin who cling to their beliefs amid anxiety; by the log cabins of Lovozero, the farewells of women still echo with the afterglow of rituals. Jeroen Tollens’ lens on nomadic societies reveals a profound truth: while the forms of faith may fade, cultural genes persist tenaciously in the details of life—from clothing patterns to dietary taboos, from the natural worship in camp site selection to the ritual origins of music and dance, shamanism has seeped into the collective unconscious of nomadic peoples.

IV. The Enlightenment of Civilizational Dialogue: Questioning at the Boundary Between Reason and Intuition

When we view shamanic beliefs through the "rational" lens of modern civilization, we should not see "backwardness" or "ignorance" but rather alternative dimensions of understanding the world. Nomadic peoples regard nature as a sentient partner, not a conquered object—a "non-anthropocentric" worldview that offers a mirror for the ecological crises of modern society. As the text suggests, stripping away the filters of education and modernity, the boundaries between "reason" and "intuition," "nature" and "the supernatural," may be nothing more than cognitive prejudices. On the snowmobiles of Murmansk, the figure of young Jasjia returning to her old camp with her father symbolizes not just a collision between tradition and modernity but a starting point for civilizational dialogue. Nomadic cultures that persist in the tide of globalization offer indispensable pieces of the puzzle for human civilizational diversity through their unique spiritual maps.

Looking back from the vantage point of the 21st century, the light of the shamanic world may no longer shine as brightly as before, yet it still flickers in the gestures and expressions of nomadic peoples. It reminds us that alongside technological progress, we must preserve a sense of awe for the unknown, humility toward diverse civilizations, and an eternal quest for the origins of the human spirit. When we in cities are confined by the steel forests, those chants and drumbeats that have traveled through millennia may just be the ancient cipher to awaken the wildness and poetry within our souls.